Senator Holds Follow-Up Hearing to Address Overuse of Solitary Confinement; Juvenile Law Center Submits Written Testimony

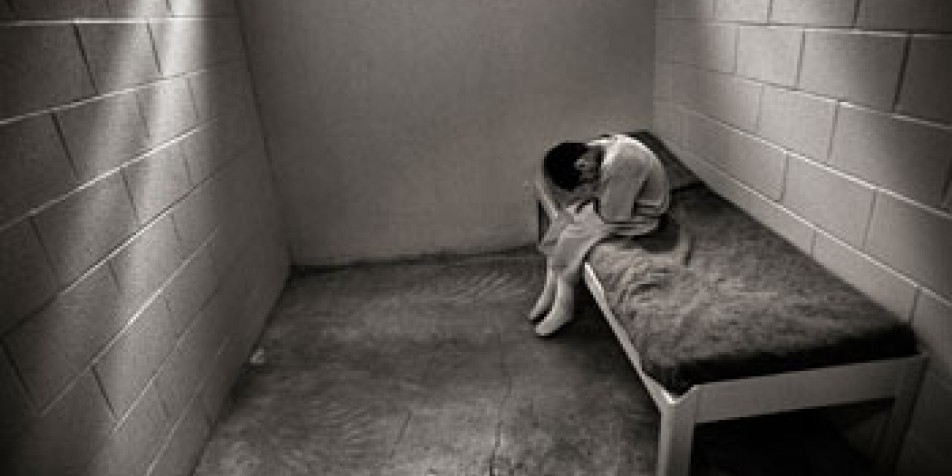

Photo via Steve Liss Photography

The United States holds more prisoners in solitary than any other democratic nation. To address this issue, in June 2012, Senator Durbin chaired the first-ever Congressional hearing on solitary confinement, featuring expert testimony on promising reform efforts that have reduced the use of solitary confinement, while also lowering prison violence and recidivism rates, and saving millions of dollars.

On February 25, Senator Durbin is holding a follow-up hearing to explore developments since the 2012 hearing and what addition steps must be taken to curb the overuse of solitary confinement while controlling costs, protecting human rights, and improving public safety.

Like our colleagues at Campaign for Youth Justice, the ACLU and other organizations, we strongly advocate for reform in this area. In particular, we believe that strong federal policy must be put in place to limit the use of isolation for juveniles in federal, state, and local facilities, and in juvenile as well as adult institutions.

Juvenile Law Center Supervising Attorney Jessica Feierman and Staff Attorney Kacey Mordecai submitted written testimony for this February hearing. Our testimony is as follows:

Juvenile Law Center Testimony on Use of Solitary Confinement for Juveniles

Our client, T.D., was 15 years old when he was first placed in solitary confinement in a juvenile justice facility in New Jersey. He remained there for almost 7 months. He was held in a seven-by-seven foot cell, alone, with no pen or paper, no books, no audio or visual stimulation. He was often denied clothing or provided a 'ferguson gown'—a Velcro-strapped garment that severely restricted his physical movement. He was occasionally denied sheets, blankets, or even a mattress. He was rarely let out of his cell, spending 23 or 24 hours a day there, his only respite a shower.

|

The United Nations Human Rights Committee has found that isolation of prisoners may be considered torture. |

T.D. was purportedly isolated to address his mental health issues. Yet despite noted diagnoses of serious mental health issues upon intake, he received almost no individual therapy, never received group therapy, and was denied the opportunity to speak with the psychiatrist about his medications. Even when staff documented that T.D.’s behavior was appropriate for weeks at a time, they continued to hold him in isolation because of his past behavior.

At almost the same time, the Juvenile Justice Commission of New Jersey was also holding 16-year-old O.S. in isolation for minor behavioral infractions such as cursing or fighting with other youth—even when he was the victim. Over and over, O.S. received “pre-hearing room restriction,” a category of punishment that allowed facility staff to place him in isolation for days at a time before even giving him a hearing.

Extensive research has demonstrated that prolonged isolation can be devastating, even to healthy adults.1 Juveniles are developmentally more immature and vulnerable than adults, and experts agree that adolescents “are at particular risk of such adverse reactions”2 from prolonged isolation and solitary confinement. National and international standards also recognize the harms of isolation. Indeed, the United Nations Human Rights Committee has found that isolation of prisoners may be considered torture.3

After much time, and significant advocacy, Juvenile Law Center settled a civil rights action on both boys’ behalf against the Juvenile Justice Commission and the mental health providers. But hours of litigation to ferret out the facts for individual cases cannot be the answer to a widespread systemic problem.

We need strong federal policy limiting the use of isolation for juveniles in federal, state, and local facilities, and in juvenile as well as adult institutions. Such a prohibition should be accompanied by policies that support positive behavioral interventions and effective mental health treatment for confined youth. This work will improve outcomes for youth, which in turn, protects public safety.

1 See, e.g. Stuart Grassian, Psychopathological Effects of Solitary Confinement, 140 Am. J. Psychiatry 11 (1983); Stuart Grassian, Psychiatric Effects of Solitary Confinement, 22 Wash. U. J.L. & Pol'y 325 (2006).

2Am. Acad. Of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, Policy Statements: Solitary Confinement of Juvenile Offenders.

3 Interim Rep. of the Special Rapporteur of the Human Rights Council on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or

Degrading Treatment or Punishment, 18, 23, U.N. Doc. A/63/175 (July 28, 2008).